Key facts:

It is a mistake to equate the fight for individual privacy with the State’s fight for security.

What matters about technologies is not their purpose, but the scope of their fair applicability.

The Internet of the future could be regulated by a global database that links people’s real-world identity to their virtual identity on the web. One proponent of such regulation, such as Bill Gates, argues, though not without reservation, that freedom of expression is not an unquestionable principle. That it is not an axiom.

For the Microsoft entrepreneur and technologist, the boundaries between freedom of expression and disinformation are blurred. Especially in the United States, where the notion of freedom of expression is deeply ingrained. first amendment and there seems to be no exceptions to its application.

Gates saysrightly so, that freedom of expression combined with the anonymity that the Internet provides is a risk factor, and a renewable source of deception and misinformation. Paraphrasing him, freedom of expression and anonymity on the Internet give “license to lie” and to say anything.

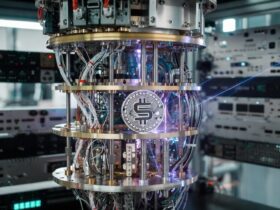

In this light, should there be exceptions to the unconditional defense of freedom of expression? Bill Gates sees a future where yes. Where Digital identification technologies will act as a layer of the Internet capable of regulating and filtering behavior of individuals:

“Most of the time you’re online, you want to be in an environment where people are truly identified. That is, they’re connected to a real-world identity that you trust, rather than just people saying whatever they want.”

Bill Gates, co-founder of Microsoft.

Regardless of whether an individual has the right to lie or not, these identification technologies are supposed to change people’s relationship to lying. In other words, they will help revoke the “license to lie” that is supposedly inherent to anonymity, even if this license is curiously overused by minorities and by power groups concerned with propaganda.

How will these technologies help to build the regulated communication society of the Internet? It is simple: if my real identity, closely linked to my physiognomy, and my personal data precede my communications on the Internet, I am objectively responsible (in front of others) for what I say.

Responsible for the truth, the lie, and the weight of the effect that my expression has on others. Also responsible for the misinterpretation that others may have of my statements.

What would a future Internet with mandatory identification look like?

My hypothesis is that just as identification technologies would revoke the “license to lie,” they would also revoke the permission to tell the truth, which is only possible without martyrdom through anonymity. The regulated internet of the future would rather authorize, to remain silent and abuse omission in speechactions that are not lies in themselves, but that help to preserve them.

The Internet would function like a social party where everyone shows their faces and where, fearing real reprisals, everyone is afraid of igniting the combustion of other people’s fury. It would function less like the masqueradeswhich exceptionally allowed that same society, but at night, to give free rein to other tendencies that were no less real, necessary and irrepressible because they were more hidden from the light of day.

Identification technologies will combat the “lies” that arise from the freedom and security that anonymity provides; just as today the right to privacy, whose main guarantor is intimacy, fights to free the “truth” from its natural fear of reprisals.

It seems, then, that anonymity is a neutral force that changes at will: it becomes positive and takes the name of the right to privacy if it protects the innocent from reprisals, and negative if it distances the criminal from justice.

Opposites collide underground, and both struggles are susceptible to degenerating into abuses and extreme positions. It would be a mistake on my part, however, to equate both struggles by granting them the same level of legitimacy, as can be understood from now on.

What matters about technologies is the scope and fair applicability

An embodiment of the abuse of the first, the right to privacy, is the identification technology called ChatControlwhich proposes monitoring and decrypting communications on high-risk messaging services, such as WhatsApp or Telegram. The use of spyware Pegasus by several governments belongs to the same category.

A more legitimate use of identification technologies is with algorithmic predictive policing systems when they are used to predict attacks by criminals and murderers with known histories, all before they occur.

Some privacy technologies, on the other hand, have useful and fundamental applications, such as virtual private networks (VPNs), which guarantee the right to privacy when browsing the Internet.

Under the more than reasonable pretext of preserving the anonymity of the community, anonymous payment technologies such as Monero can be used by individuals to hide transactions that launder or move “illicit” money.

Except for a few technologies deliberately created and designed to kill or harm, such as chemical and biological weapons whose effect is irreversible, or ancient and spectacular ones such as the gallows, most of them fall into relative territory.

Regardless of its purpose or even the ideology that animated its design, The essence of a technology is the scope of its practicality for the majority of casesIn this sense, proponents of identification technologies to deanonymize the Internet should not believe that they are merely fixing problems without first asking themselves about the scope of applicability of their solutions.

It is more realistic to believe that they are creating new problems, temporarily reversing the weights on the scale of values. New and legitimate problems, by the way, because I do not consider that eternalizing any value is the answer.

A pen of 10,000 sheep to catch 6 wolves

Now, if I stick to global statistics, some indicate that, on average, until 2020, there were 6 intentional homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in the world. The countries that are worst off by the measurement are South Africa, Myanmar, Jamaica, Honduras and Colombia, with 42, 28, 52, 38 and 27 for the same number of inhabitants, respectively.

Even when murders are high in those countries, The number remains a flagrant minority of acts and criminals per 100,000 inhabitants. There are certainly many more common criminals than murderers, but it would not be unreasonable to generalize these data to conclude something obvious and already known to everyone: Outright criminals (or rather, outright criminality) are a minority. Hence, equating the fight for individual privacy with the fight for national state security constitutes a serious error of equivalence that takes away more freedom from the individual, who is not free, and gives more power to the state, which is already powerful.

If the relationship between data and identification technologies is not clear enough, I will leave with two questions that should clear up any doubt: with crime being so little widespread, is the scale and extent of application of identification technologies, such as ChatControl, justified? Is “justice” done when, in order to catch six disguised wolves, ten thousand sheep are isolated in a pen?

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of CriptoNoticias. The author’s opinion is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or financial advice under any circumstances.

Leave a Reply