The Ministry of Health and Child Care has announced that the current cholera outbreak has affected the districts of Bikita, Bindura, Chiredzi, Chipinge, Kariba, Goromonzi, Mazowe and Shamwa.

Glendale, a farming town in the Mazowe district, about 70 kilometers north of Harare, is one of the epicenters of the cholera outbreak. Residents there are appealing to the government to take immediate action to stop the spread of the disease.

People there are forced to live in mud ponds after burst pipes were left neglected by the government for months. Disease agents carrying human waste are apparently contaminating freshwater sources in Glendale and beyond in this manner.

contaminated wells

On December 26, 2024, 10 members of a family in Glendale had to be taken to the Tsungubwe Cholera Treatment Center after showing symptoms of the waterborne disease.

The Nyirongo family has relied on their shallow well as their main source of water for years, but recent rainfall across the country has led to sewage entering the underground water supply.

“It rained heavily for two consecutive days on December 24 and 25… causing our well to be polluted with sewage, possibly even before that,” Erekta Nyirongo, 71, told reporters.

“We hope that they will provide us with clean water in the future to avoid these diseases.”

Throughout Zimbabwe – including the capital Harare, there is currently no reliable water source due to raw sewage flowing into people’s water sources amid the overall poor condition of the water system.

One death and some solutions

Zimbabwe’s Deputy Minister of Health and Child Care, Slimane Timios Quidini, recently visited Mazowe District to assess the extent of the cholera outbreak, after one person died from the disease there.

Quidini says the government has partnered with other organizations to drill two boreholes in Glendale – but will it be enough for everyone?

Quidini believes some local wells may remain in use because the government is planning to make available “tablets that will actually help kill the bacteria found in the water.”

“In addition, we are encouraging our community to boil water, even if it’s coming from a clean or protected water source… to reduce our chances of contracting cholera.”

The deputy minister further explained that after inspecting the toilets in the communal bathing blocks, he found that these facilities were “not properly located.”

“So we have agreed that we will set them where it is appropriate so that they are not mixed, where they have access to water and toilets.”

However, it is unclear how long it may take to implement these reform plans.

Hygiene first!

Kudzai Masunda, a public health expert at the private voluntary health organization JF Kapnek Zimbabwe, is also calling for improved hygiene practices in households but also at the community level as part of overall efforts to prevent cholera.

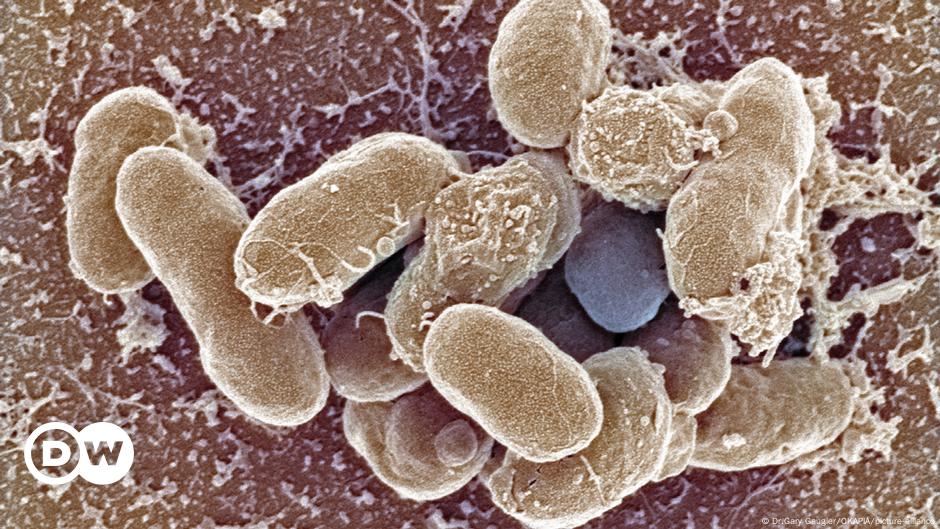

Masunda, who also serves as secretary general at the Zimbabwe College of Public Health, said, “Cholera is primarily a water-borne disease and also a fecal-oral transmitted disease, meaning people become infected through what they eat. “Hygienic practices are therefore important.” doctor.

“If we want to eliminate cholera, we have to improve water and sanitation in our suburbs and rural areas because previous cholera outbreaks have also occurred in rural areas.

“One of the short-term measures already taken to eliminate cholera is the use of vaccines to ensure that we reduce the incidence of cholera for at least three to four years, while we continue to improve water and sanitation Want to improve what needs to be done.”

Masunda said the whole of Africa is vulnerable to the disease, with cases of cholera reported in Burundi, Cameroon, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The last cholera outbreak in Zimbabwe occurred in 2023, affecting a total of 62 districts from all 10 provinces of the country, according to WHO.

During the outbreak, the country recorded 34,549 suspected cases, 4,217 confirmed cases and 33,831 recoveries.

According to WHO, the worst cholera epidemic in the country was recorded in 2008 and 2009, resulting in approximately 100,000 confirmed cases and 4288 deaths.

Edited by: Serton Sanderson

Leave a Reply