In 2016, Hershel Hepler was browsing Google Images to practice his paleography – the study of historical writing systems – when he stumbled upon an Airlie family photo that would lead to a groundbreaking discovery.

“I recognized it immediately and said, ‘This is a manuscript in our collection,'” recalls Hepperer, a curator at the Museum of the Bible in Washington.

The museum had recently acquired the manuscript – a rare Jewish prayer book – believing it to be part of the famous Cairo Genizah, a trove of ancient Jewish documents uncovered in a Cairo synagogue in the late 19th century.

but in black and white pictures Gun Shot The magazine described the manuscript as “a 16th- to 17th-century Hebrew Book of Psalms, said to be from the Bamiyan region of central Afghanistan.

Stunned by the revelation, Hepper sets out to verify it. tracking the author of Gun Shot In the article, British historian and archaeologist Jonathan Lee, Hepler confirmed that Lee had indeed found the book in the possession of an Afghan warlord in 1998 and had photographed the cover and two inside pages.

“Without Jonathan’s documentation from his visit to Bamiyan in 1998, we would still assume it is probably from the Cairo Geniza,” Hepperr said.

But if Hepper was surprised to learn of the book’s origins in the remote mountains of Afghanistan, Lee was equally stunned when Hepper revealed that the manuscript was carbon-dated to the 9th century. Was.

“At that time, I realized that the discovery was of great significance,” Lee said via email.

Recognizing their combined expertise – Hepper in Hebrew manuscripts and Lee in Afghan history – the pair joined forces and invited in other experts.

His years of research not only established the manuscript as the oldest-known Hebrew book, but did reveal that Jews had lived in Afghanistan and along the ancient Silk Roads for much longer than historians had previously known.

But the thrill of the discovery was tempered by the realization that the manuscript had probably been smuggled out of war-torn Afghanistan and sold on the antiquarian market.

At the time, the museum, founded by the Green family, owners of the Hobby Lobby Arts & Crafts Company, was still growing from the acquisition of smuggled artifacts from Iraq and Egypt.

The museum faced a significant challenge: before it could show it to the world, it needed to legalize its ownership of the manuscript. For delicate negotiations with New York’s small Afghan Jewish community and with an Afghan government on the brink of collapse. The stakes were high, and the path to securing the manuscript’s rightful place in the museum would prove very complex and demanding.

Lee’s discovery

Lee, who has spent the better part of the last five decades researching and writing about Afghan history and archaeology, discovered the book by chance.

In April 1998, he was guiding a Japanese TV crew to Bamiyan in search of Bactrian language inscriptions and gold coins looted from an ancient Buddhist shrine.

At the time, the Bamiyan Valley, with its famous Buddha statues still standing, was controlled by a local Shia rebel group, while the Taliban ruled the rest of the country.

The leader of the anti-Taliban group, Karim Khalili, kept a collection of antiquities, among them a cache of gold coins. Lee took his picture.

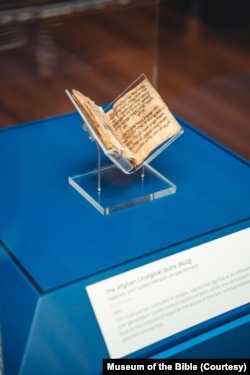

“Then, his [Khalili’s] Consultants brought in a diverse collection of other antiquities, including the ALQ,” Lee said, short for “Afghan Liturgical Choir,” the Hebrew book in the Museum of the Bible’s collection.

A local man associated with the Shia rebel group had found the book under a collapsed ceiling in a cave the previous year and given it to Khalili.

Unversed in Hebrew, Khalili apparently showed the book to other foreigners visiting Bamiyan, trying to find out what was what.

“I was told it was found in Bamiyan, but then everything is higher in Bamiyan,” Lee said.

As Lee recalls, the pocket-sized book looked remarkably well-preserved for its age.

“The covers were somewhat folded, damaged, and watermarked, but the folios were relatively well preserved, and most of the text was readable,” he said.

To Lee, this suggested the manuscript was “not that old.” He left Afghanistan and didn’t think much of it for years.

How and when the manuscript left Afghanistan remains unknown.

The 1990s were a dark period for Afghanistan’s rich cultural heritage. As armed groups fought in the region, their men – often guided by their commanders and smugglers – looted the country’s vast archaeological sites and ransacked its museums. Seventy percent of the National Museum’s treasures disappeared, according to one estimate, with many ending up in private collections and some prestigious institutions.

“The country has a long history of illegal export of antiquities that goes back decades, but ultimately goes back to colonial times,” said University of Chicago professor Cecilia Palombo.

A leading researcher with extensive experience in Afghanistan said that the manuscript was taken out of the country after the Taliban overran Bamiyan in late 1998. The researcher spoke on condition of anonymity.

Research at the Bible Museum found that an unnamed Khalili deputy made several sales attempts in the United States and Europe between 1998 and 2001, “apparently” landing it with a private collector in London. Buffed it up in 2013 and donated it to the museum.

The office of Khalili, who later served as vice president, declined a VOA interview request.

Gun Shot Article

Although Lee had found the book in Afghanistan, he had no idea how important it was. On his return to England, he showed the photograph to a Hebrew expert, who thought it was from the 16th or 17th century.

Then, after a cache of ancient documents called “Afghan Geniza” surfaced on the international art market, Lee decided to publish his photographs, along with an article about Afghan Jewish history. Citing the book as an example of “Jewish content” [turning up] Sometimes in Afghanistan, he wrote that “the whereabouts of this manuscript is now unknown.” ,

Hey, we will know after four years. When, “out of the blue,” Hepper contacted him via LinkedIn and told him that the manuscript was not a book of Psalms, but a prayer book, containing Sabbath prayers, poetry, and a partial Haggadah, the Jewish text. Told in the Passover.

The Green family acquired the book from an Israeli antiquities dealer during their purchase of ancient artifacts in 2013. Some of these items were later returned when it was discovered that they contained illegally sourced beeswax from Iraq and Egypt.

Tracing the manuscript to collectors in London in the 1950s, the Afghan Liturgical Choir came up with its own provenance, masking any connection to Afghanistan. With Lee’s documentation, the museum was able to recover its provenance.

The museum initially thought the book was from the 9th century, but a second carbon-dating test in 2019 showed it dates to the 8th century, making it the oldest-known Hebrew book in the world. older than two centuries.

The discovery electrified experts.

For Hebrew scholars, the discovery offered the earliest evidence of a bound Hebrew book.

For the Afghanistan specialist, it highlighted “how important this region was in relation to the history of Afghanistan’s ancient connectivity with the cultures and religious traditions of the Middle East, Inner Asia and Northern India,” Lee said.

Yet the realization that these bees were smuggled from Afghanistan cast a cloud over its validity.

Afghan law and the 1970 UNESCO Convention make it illegal to export cultural artifacts and heritage items without government approval.

To legitimize its custody of the manuscript, the museum adopted what it calls a “human rights-based approach” to cultural heritage.

Invoking the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the museum argued that Afghan people and Afghan Jews living in New York have the right to access the manuscript.

“One of the things the focus of this project is, Sun, is outreach to the Afghan Jewish community, outreach to the people of Afghanistan,” Hepper said.

To support both stakeholders, the museum initiated discussions with former Afghan government officials and members of the Jewish community in New York.

Theses efforts culminated in the signing of a memorandum of understanding in 2021 with the Afghan Embassy in Washington, which Dolde was held under mentorship before the Taliban takeover.

The Afghan ambassador at the time, Roya Rahani, did not respond to a request for an interview. Another former Afghan ambassador wrote a letter of support for the project.

Afghan Jewish Federation head Jack Abraham, who was born in Afghanistan, said his group gave its full support to keeping the manuscript in the United States.

“I told [Hepler]’What is in your hands is our inheritance. This is for us. It could have been any one of our ancestors,” Abraham said.

But some Afghans see it equally as part of their heritage.

A senior former government official said, “This is Afghanistan’s property and should be returned to Afghanistan.”

Barnett Rubin, a leading Afghanistan scholar and advisor to the ALQ project, said that both communities can legitimately lay claim to the book.

“The museum wanted the approval of one of the two main entities that could claim it for custody,” Rubin said.

With a preservation agreement in place, the museum celebrated the project as an interfaith collaboration between Jews, Christians and Muslims, to go on display in September.

A second demonstration is planned for New York starting this month.

While the Bible Museum technically owns the manuscript, Hepper said Afghanistan and the Afghan Jewish community “have a lot of agency in this custody.” To that end, the museum plans to provide one high-quality replica to the Jewish community and three to Afghanistan’s major cultural institutions.

Leave a Reply