Under the yellow autumn sunshine, the sounds of children crying mingle with the rumble of truck engines at the Chaman border crossing in southwestern Pakistan.

Afghan families who have been living in Pakistan for decades are now being forced to leave with only a few belongings including blankets, furniture, cooking utensils. Their heartbreak travels with them.

42-year-old Zahra is also among those waiting to enter Afghanistan. She is completely covered with a blue burqa and holds her youngest daughter close to her.

Families like Zahra’s are caught in a whirlwind of uncertainty amid Pakistan’s pressure to expel the Afghans, which has escalated after intense and deadly border clashes with the Taliban last month.

“I was born in Pakistan. My parents came here during the Soviet war,” he told DW. “I don’t know anyone in Afghanistan, but the authorities have told us to leave.”

Life in danger due to sudden explosion

Millions of people fled Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion in late 1979.

Zahra’s parents and over a hundred members of her extended family were among those who made the journey, with the couple settling in a refugee village in Quetta, south-western Pakistan, where Zahra was born and raised.

This month, Pakistan announced plans to close all 54 Afghan refugee villages across the country as part of an ongoing campaign starting in 2023 to expel what it refers to as “illegal foreigners.”

The decision affects villages in Quetta – Zahra’s family home.

Activists argue that the policy is overly harsh and was implemented suddenly, leaving families with no place to live.

Aziz Gul, a Pakistan-based Afghan human rights activist, told DW, “The sudden expulsion of Afghan refugees by Pakistani police has put the lives of dozens of people in danger. People who had fled to Pakistan to escape terror, persecution and violence are now falling into the hands of the Taliban regime because of Pakistan’s actions.”

Pakistani officials ‘more brutal’ after border fighting

Many other Afghans sought refuge in Pakistan following the 1990 civil war, the US-led invasion in 2021, or the Taliban takeover in 2021.

There was a time when Pakistan’s generosity towards refugees was a matter of national pride. However, amid the increasingly bitter dispute between Islamabad and the Taliban regime, and especially after the clashes in October, the Pakistani government is stepping up expulsion efforts and labeling undocumented Afghans a security risk.

“The Afghan Taliban have made life more difficult for Afghan refugees, who were already in a difficult place, by starting border skirmishes. The Pakistanis have become more determined with the expulsion program, I can say they have become more brutal,” Osama Malik, a senior humanitarian and refugee law expert, told DW.

Taliban leaders in Kabul blame Pakistan for the border conflict, which has killed several people since it first erupted nearly four weeks ago. While both sides have officially agreed to a ceasefire and are engaged in peace talks in Istanbul, fresh gunfire on Thursday reportedly left at least five people dead on the Afghan side of the border.

‘We are born in this country’

Over the past few years, Afghan immigrants have established new lives by enrolling in Pakistani schools, joining cricket clubs, starting small businesses and renting homes in cities such as Karachi, Quetta and Peshawar.

“We were born in this country and have built our lives here, so it was a sudden shock to hear that we must leave. We have never set foot in Afghanistan and we don’t know where we will go,” Abdul Rehman, a 44-year-old fruit vendor from Quetta who has torn down his home in preparation to return to Afghanistan, told DW.

“My children are enrolled in Pakistani schools and speak Urdu, and my daughter’s education will be terminated in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. They watch Pakistani TV shows and series. How will they survive there?” He said.

Pakistan’s hospitality ended

The United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, has criticized Pakistan’s decision to forcibly repatriate Afghan refugees, including those holding Proof of Registration (POR) cards and officially in need of international protection.

“We are concerned about women and girls being forced to return to a country where their rights to work and education are at risk,” Qaiser Khan Afridi, a UNHCR spokesperson in Pakistan, told DW.

Afridi praised Pakistan’s generosity and “proud history of hospitality”, saying this tradition should continue.

However, as Pakistan is facing an economic crisis, political instability, and military conflict, many ordinary Pakistanis have complained about Afghan refugees. Locals often accuse Afghan migrants of competing for employment and housing, while officials publicly link them to crime and terrorist networks.

“For four decades, we have welcomed Afghans to our country, showing our hospitality and generosity. But this cannot continue indefinitely, and eventually they will have to return. Additionally, any foreigner living in the country illegally will be immediately deported,” senior Pakistan Interior Ministry official Talal Chaudhry told DW.

Female medical student travels to Afghanistan

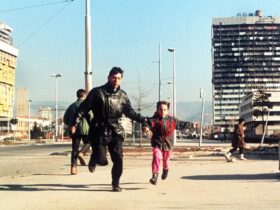

In makeshift camps near the Chaman crossing, long queues of vehicles line the dusty grounds as people wait for hours before entering Afghanistan.

“We left our home in Quetta two days ago and are going to an unfamiliar place,” says Fatima, a 22-year-old medical student. “I had to abandon my studies because I did not have the necessary documents. My dream was to work in a hospital, and now I am unsure of my future in an undemocratic country where girls’ education is banned.”

Across the border, Taliban-ruled Afghanistan is already facing a severe humanitarian crisis, including food shortages, severe winter conditions and harsh restrictions on public life, especially women.

“Afghanistan is not prepared to handle such a large number of returnees,” says Afridi, the UNHCR representative. “Most families have nowhere to go, and many are still returning to areas torn by conflict.”

living between two worlds

As the sun sets over the mountains near the border, children play around trucks loaded with their families’ belongings. Their laughter briefly covers their parents’ disappointment.

Zahra’s eyes are fixed on the horizon.

“We’ve crossed a lot of frontiers in our lives. But this feels like the final frontier,” she says.

As his name is called, his family moves forward. Within minutes, she disappears into the flow of people headed for Afghanistan, a land they have never seen, a future they cannot fully imagine. The graves of his parents remain behind.

For the Pakistani government, deportation is a matter of state policy. For families like Zahra’s, they mark the end of a life spent hoping to survive in a country that has rejected them.

Edited by: Darko Janjevic

Leave a Reply