In March 1938, paramilitary groups in leather boots and brown uniforms marched through the streets of Vienna. Part of Adolf Hitler’s Sturmabteilung (SA), they were celebrating the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany. As two SA members hung a sign reading “I am a Jewish Pig” around the neck of an old woman, a man moved through the crowd to help her. A scuffle broke out but the man was lucky to escape. It was dangerous to oppose the Nazis at that time, and he had to go to jail.

But because of his name he did not remain behind bars for long. After all, Albert Göring was the brother of Hermann Göring, Supreme Commander of the Air Force, and one of Hitler’s closest confidants. Nevertheless, unlike his brother, Albert was actively involved in opposition to the Nazis. “What he saw went against everything he believed in and he had no choice,” says William Hastings Burke, author of the book “Thirty-Four: The Key to Goring’s Last Secret.”

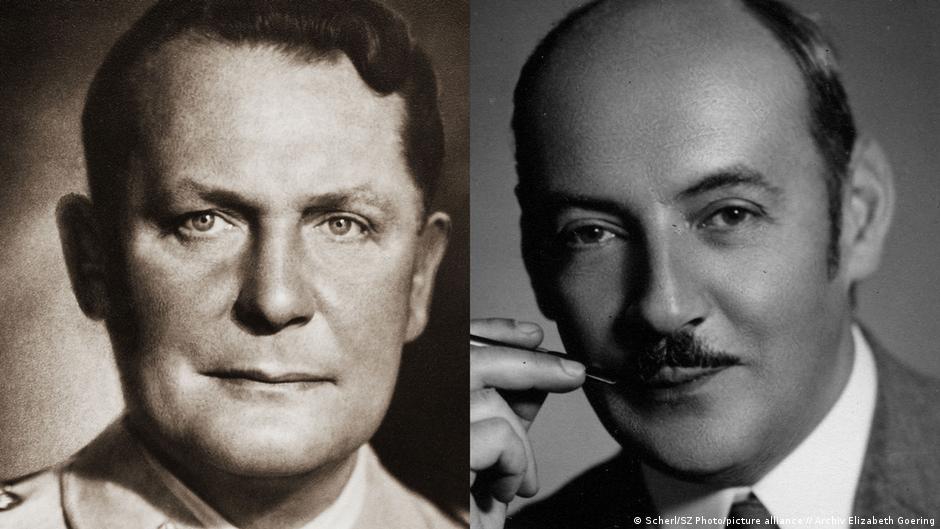

brothers, but polar opposites

How can two brothers be so different? Hermann was power-hungry and narcissistic, while Albert was a charming bon vivant of Nazis like Oskar Schindler. While Hermann was already a supporter of Hitler by 1922, Albert had no political ambitions of his own and rejected Nazi ideology and its brutality.

A mechanical engineer, Albert moved to Vienna in 1929 and joined the film industry as technical director at Tobis-Sascha Filmindustrie AG in the early 1930s. He was concerned about developments in Germany, where the Nazis were persecuting and dehumanizing Jews and political opponents. It may seem strange, but it was actually Harman who asked his younger brother to help actress Hennie Porton get a movie role, says William Hastings Burke. Porton was a star of the silent film era who could no longer work in Germany because she refused to leave her Jewish husband. Henny was also a friend of Herman’s wife Emma and Albert was happy to help.

helping Jews escape

Two years later, Joseph Goebbels – the Nazi Propaganda Minister – wanted to integrate the Tobias-Sascha film production company into his propaganda machine. Albert’s former boss, Oskar Pilzer, was one of the most successful film producers in Europe before the Nazis enacted employment restrictions for Jews. When the Gestapo came to arrest him, Albert intervened and personally accompanied Pilzer to the Italian border.

This was not the only time Albert helped others escape. While his brother worked on expanding the German Air Force, Albert forged documents, arranged escape routes, and provided money to escapees. His nickname often came as a shock to many Nazi officials. He also intervened on behalf of the composer Franz Lehár, whose wife Sophie was Jewish. He asked Hermann to register Lehar’s marriage as a “privileged mixed marriage”, thus saving Sophie from deportation to a concentration camp.

Hermann Goring’s priorities

For these rescue operations Albert Göring often sought the help of his powerful elder brother, who was, unsurprisingly, beholden to Hermann Göring. Despite his ruthlessness as a politician, Burke says, he was generous when it came to his family. “In fact, Albert was a huge headache for Hermann. But I think Hermann had no choice because he was his brother, he loved him and could not sacrifice him.”

Burke says that Hermann had a clear hierarchy: he came first, followed by his family, the Fatherland, Nazism, and Hitler. Burke explains, “He was like the godfather of the family. He was fueling his ego, but he was also working on behalf of his family, helping his brother.”

In 1939, Albert was appointed export director at the Skoda Works in Brno, then Czechoslovakia, which was under Nazi occupation. “A lot of people said that Albert started working at Skoda because his brother had the power and gave him the job,” Burke explains. Although he believes it was probably the opposite, the Czechs believed that having “someone with direct access to the big boss in Berlin” could help protect their interests.

Under Gestapo surveillance

Albert fulfilled those expectations. He stood up for the Czechs and actively supported the Czech resistance by passing on secret information such as the exact location of submarine docks or plans to break the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. He received this information through his business contacts and his brother.

According to eyewitness reports, Albert continued to help others escape the Nazi regime. It is said that he picked up Jewish prisoners from Theresienstadt concentration camp to do “war-essential” work at the Skoda Works. Jacques Benbasat, One of the few surviving witnesses who knew Albert Göring closely and extensively, mentioned Burke“The concentration camp wardens agreed to this because the request came from Albert Göring. The trucks would stop in a forest, and their passengers would be allowed to escape.”

But Albert’s actions became increasingly reckless and he came under the radar of the Gestapo for a long time and was eventually declared an enemy of the state. Nevertheless, he was not imprisoned because of the protection of his brother Hermann. William Hastings Burke explains: “In October 1944, when Hermann Göring’s power in the Third Reich was at an all-time low, he still risked his political neck by coming forward and helping to save and intervene on Albert’s behalf.”

The curse of the Goring name

The brothers’ loyalty remained unchanged. After the fall of the Third Reich, both men were imprisoned. During interrogation, Albert refused to speak ill of Hermann and praised his “warm-heartedness”. Americans did not believe that Albert himself was not a Nazi. William Hastings Burke explains, “So the same name that enabled him to save people ultimately ended up contributing to his own downfall. It was a curse.”

On September 19, 1945, American investigator Paul Kubala wrote: “The results of the interrogation of Albert Goring… are as clever a piece of rationality and ‘whitewashing’ as the SAIC (Seventh Army Interrogation Center) has ever seen. Albert’s lack of subtlety is matched only by his fat brother.”

The “Thirty Four” of the title of Burke’s book actually refers to the 34 names that Albert Göring listed in alphabetical order, which he described as, “people whose lives I saved at my own risk (three Gestapo arrest warrants!).” No one tried to find the people included on Albert’s list – although it included high-profile names.

However, things changed for Albert when a new interrogating officer took over his case: Victor Parker was the nephew of Sophie Lehr, who was also on Albert’s list. While Hermann Göring committed suicide the night before his scheduled execution, Albert Göring was released. But Burke says, “He was untouchable in his own country because of his name.”

After the war, Albert could find no employment as an engineer and survived by doing odd jobs and translating. A social outcast, he remained isolated from society until his death in 1966 at the age of 71.

Albert Goring as a role model – even today

“It’s a very sad story,” says William Hastings Burke, who has been fascinated by the story since he first heard about it in a TV report. Burke traveled to Europe and researched material on Albert Göring, combing through archives and meeting former associates or relatives of people whom Albert had helped. He also discovered his grave.

Burke explains, “I thought, I should tell the world about this guy.” His book may have been published in 2015 but Albert Goring is still on his mind. For him, Albert is a role model: “Albert was a man who stood up against this regime. But after the war, he didn’t go and tell the world about it. He wasn’t interested in fame; he just preserved his humanity.”

Although Burke says that 1930s Germany cannot be compared to today’s world, “I think it’s a very powerful example of what is really important for today.”

In fact, Burke has submitted a request to the Yad Vashem memorial to list Albert Göring as “Righteous Among the Nations”. He hopes that one day it will be approved.

This article was originally written in German.

Leave a Reply