“Come on, toothworm, don’t drink any more blood!” – Long before antibiotics, anesthesia and X-rays changed the face of medicine, physicians around the world may have tried to explain away diseases with words in similar ways.

In the Middle Ages, chants were used to directly address disease “demons” or body parts, such as plague spirits or the “wandering womb” – which were blamed for stomach pain or infertility. The idea of this personification was to threaten the alleged source of the disease and persuade him to leave the body.

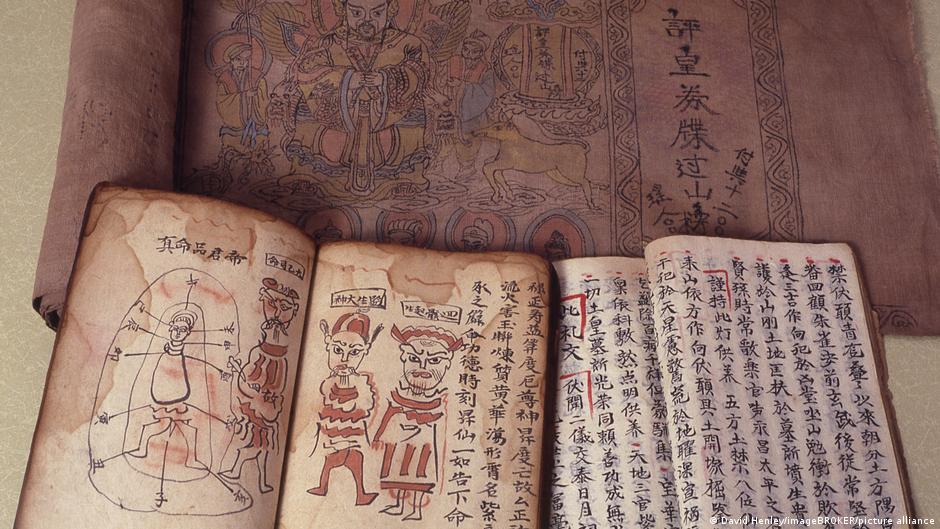

To this day, mantras continue to be used in folkloric medicine or religious rituals throughout the world, mostly in combination with herbs, massage, and other treatments.

fight monsters

One of the oldest examples comes from the ancient region of Mesopotamia, primarily present-day Iraq. In a source from around 1800 BC, the “tooth worm” is described as living between the tooth and gum and drinking the blood of its host before being killed by the “strong hand” of Ea, the god of wisdom. To cure the problem, a mantra was recited several times and a healing ointment was applied to the tooth. The imagery of the worm served as an explanation for toothache, as well as helping to defeat an opponent – in the form of a demon – while the ointment soothed inflammation.

“The spells are used specifically for certain situations, not equally for everything,” Katherine Ryder, professor of medieval history at the University of Exeter, told DW. “These are commonly found for bleeding, epilepsy, toothache and childbirth,” he said.

For centuries, the difference between prayer and witchcraft has been a topic of heated debate. Ryder, in his book “Magic and Religion in Medieval England”, describes how religious scholars, confessors, and doctors constantly debated whether a particular formula constituted sacred prayer or forbidden magic. Chants containing Biblical quotations or the names of saints were generally tolerated, while mysterious sequences of letters were often branded as potentially demonic.

Cure for body and soul

Ryder told DW that it’s important to note that spells were used primarily as a complementary therapy, adding that “medieval medical books often listed them with other remedies such as drinks or baths so that healers and patients could choose which approach to take.”

According to the professor, the expert knowledge of symptoms and active ingredients did not contradict the mantras, but was combined into a comprehensive package designed to address body and spirit.

Even old medicine followed this dual principle, with exorcists reciting spells to ward off spirits while applying ointments, incenses, and potions, and using amulets to literally bind healing blessings on the body.

Prayers and magic spells also merged into traditional Islam. Certain verses of the Quran were believed to have healing powers and were recited over the sick, written on paper, or mixed in water drunk by the patient.

The term “hocus pocus”, often used to describe alternative treatments, is an onomatopoetic imitation of the Latin mass formula “hoc est enim corpus mum” (this is my body). However, the term is mostly used in a derogatory sense, as medical professionals often view homeopathy and shamanism as ineffective or esoteric.

the healing power of words

Words spoken repeatedly with authority – whether by a priest, exorcist, or doctor – can reduce fear, reduce pain, and strengthen the patient’s will to endure difficult forms of treatment.

Katherine Ryder is convinced that witchcraft also acts as a suggestive or psychological support for patients, similar to the placebo effect. “Most medieval doctors don’t explain them in those terms, but there is a treatise by a medieval Arab physician named Qusta Ibn Luca that describes how spells also help if the patient believes they will work. So, at least one medieval doctor recognized the placebo effect,” she said. Ryder concluded that the scholar dated 860 B.C. The placebo effect was outlined in the same year itself.

In some cultures, illnesses were believed to be attacks of spirits or angry gods. The mantras, in turn, transformed the symptoms into an understandable story. People who believed they knew which demon was responsible were better able to tolerate pain and even painful treatment.

Nowadays, fever, toothache and depression are treated with medicine, surgery and psychotherapy. And yet, the history of mantras shows how powerful words can be in times of crisis as they make the invisible and incomprehensible more understandable.

According to the Bible, Jesus is said to have told a man healed of leprosy, “Get up and go; your faith has made you well.” In all likelihood, the real miracle of these mantras is not the alleged miracle of exorcising demons, but rather the insight that healing almost always requires strong faith.

This article was originally published in German.

Leave a Reply